From the beginning with SPOR: I started groping with my passion for woodwork and carpentry after I moved to the country

Articol scris de: Policolor

The writer Marius Chivu has a special relationship with wood since he was a child and spent his holidays in the countryside, where his grandfather’s carpentry workshop seemed to him to be the most beautiful place in the Universe.

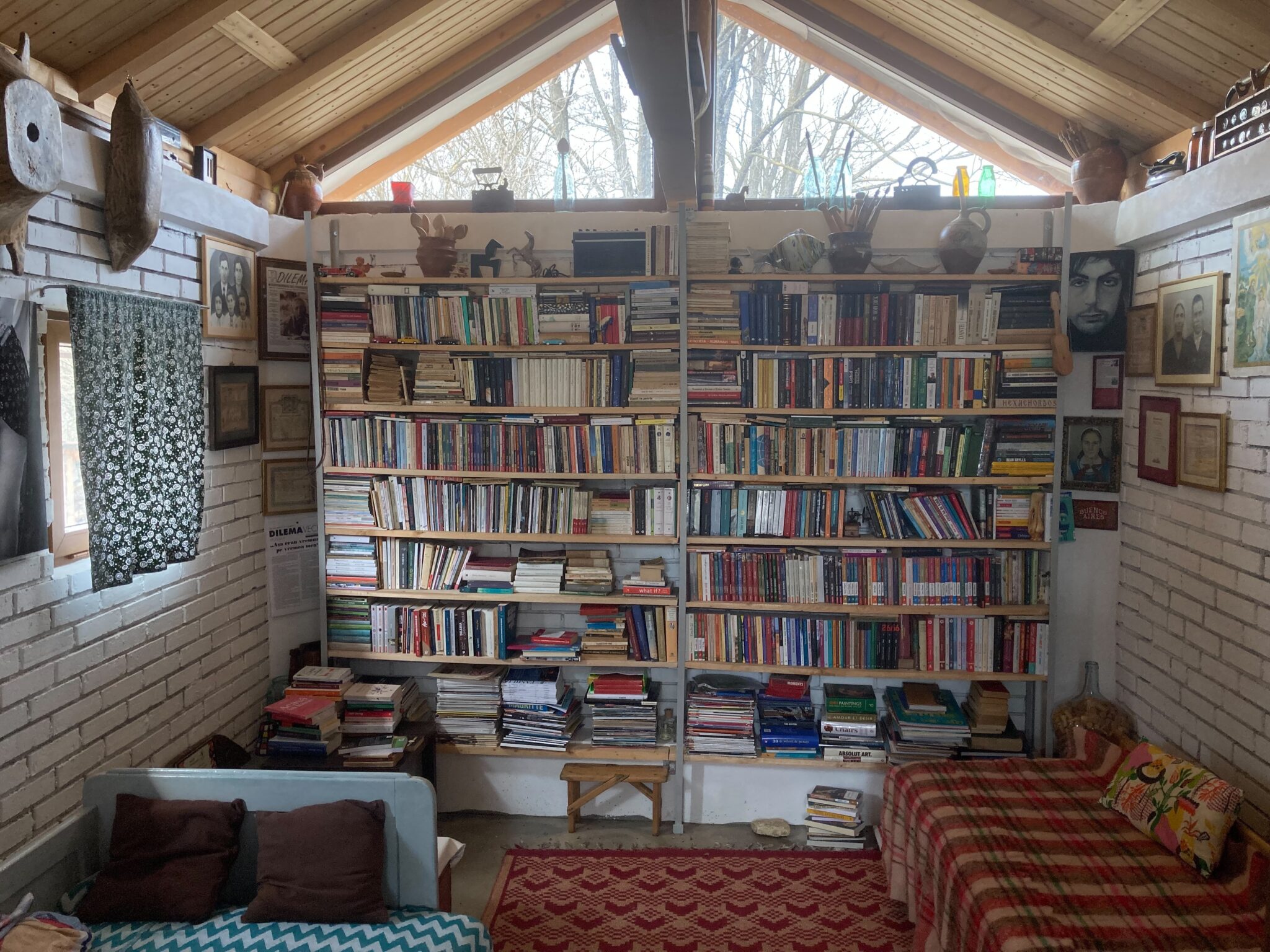

A few years later, after he renovated his grandparents’ house and moved there with the pandemic, one of the projects that brings him the greatest joy is the reconstruction of his grandfather’s workshop in the former stable, which now – in addition to the role of workshop – it is also a library.

This article is part of the “From the beginning with Spor” campaign, through which we try, together with Policolor and SPOR, to find out what makes people leave the city behind and move to the countryside.

We continue the story of the writer Marius Chivu, told by him himself.

The first refurbished parts were even grandfather Toma’s tools

The magical place of my childhood spent in the countryside, in Oltenia under the mountain, was grandfather Toma’s carpentry workshop.

In the toy shortage of communism, that workshop developed my imagination by forcing me to see in every piece of wood in the scrap heap a potential toy. There, in that workshop, from my grandfather’s hands, my first sled was born, under my eyes.

Even from that time I knew the names of the tools neatly arranged, according to need and size, on the shelf under the counter or in the nails hammered into the walls of the workshop: planer, chisel, chisel, scraper… And today, the smell of sawdust fills me with nostalgia: it’s the smell of my grandfather’s skin, perhaps the most sensitive man I’ve ever known: he caressed the wood as he worked and stopped to listen to the song of a bird in the garden. He was a perfectionist whose apprentice you couldn’t resist: he would take apart and redo a work until it came out flawless. Hence the varied and colorful, almost musical collection of swear words with which he accompanied his work. He was also an elegant fellow (grandmother called him fudul): he wore white shirts buttoned up to the last button, a felt hat and polished boots. He entered the workshop prepared as if he had gone to church

I mentioned grandfather Toma because I owe my passion for woodwork and carpentry to him, a job I really started to explore once I moved to the country , at the beginning of the pandemic.

When I renovated my grandparents’ house, one of the things I am most proud of is the fact that I was able to reconstruct his carpentry workshop in the former stable turned into a 30 square meter library. Cleaning, repairing, and displaying Grandpa’s tools (stored and strewn about after the plywood-walled workshop collapsed under the weight of a winter long ago) was my first woodworking refurbishing activity.

Grandmother’s “utensils” followed, most of which were also made by grandfather: wooden spoons, choppers, troci, putineiul, whirligigs, juicers, spindles, suveics, looms and, in general, all the components of the loom (disassembled and stored in the attic of the house), wooden pieces with which I decorated the house as ready-made objects, acquiring abstract connotations exhibited individually. (Idea taken from the extraordinary sculptor Maxim Dumitraș, the craftsman of a Museum of Comparative Art in Sîngeorz Băi, unique in his way and definitely worth a visit, even if only online at www.macsb.ro.)

#casuțelemele, the hashtag that tells the story of old people’s homes seen in recent years

While cleaning, repairing and oiling these wooden objects I had the revelation that almost everything I would need in the old house, made new by extension and modernization, must have a history. So, in the last two years, I have searched all the streets and hamlets of the commune in search of abandoned or dilapidated old houses in order to recover objects and pieces of furniture. This is how my Instagram hashtag #căsuțelemele was born, where I archived photos of all the old houses I have come across in recent years, some of which have since disappeared, been demolished or collapsed.

I also “corrupted” my father, becoming a partner in this “patrimony recovery” action of mine, as we joke. I needed him because he is very skilled at both disassembly and repair, but mostly because many large and very large items had to be towed. As happened last year when I accidentally discovered, in a wooded valley, a manor house built in 1912 whose roof had partially collapsed. The heirs were delighted that someone was interested in the things inside threatened with destruction and gave us permission to take all we wanted, all we could.

For a whole day, I worked with my father to remove chairs, tables, beds, cupboards, cabinets and hangers from under the rubble, to dismantle the cupboards, to pull the massive doors out of the cracked and tilted walls. I loaded up two trailers with WWI wooden stuff, then for a whole summer I kept them in the yard in the sun to dry the mold and air out, sanding away the stains and dirt and flaws, fixing what was broken (hinges, locks, drawers) and, finally, to give them primer, varnish or oil.

What I didn’t use as such (chairs, tables, beds) I reinvented as pieces of furniture or thought of them as decorative objects: I put mirrors on the windows, I made a bench from a wine press, I used the kits as bedside tables, I put handles on a cheese counter and thus it became a box for audio-books, I put supports on half of the bottom of a barrel and turned it into a shelf, I used slats as a curtain gallery, drawers in form of boxes for the sachets of spices.

Cleaning and treating old wooden objects is painstaking and time-consuming, especially if they were once painted or have decay. You need not only skill and imagination (which you eventually get if you follow specific tutorials, websites or social media accounts), but above all, patience.

My motivation was the sentimental connection with my grandparents and their world, I wanted to recover as much as possible, and for our house to have a museum dimension.

Another motivation coming from the disappointment of the fact that no one in my village renovated the old houses keeping the original materials, the architecture, the spirit. They replaced the woodwork with insulating panels and the floors with laminated parquet, they built the porches, the facades were insulated, and the polystyrene covered the decorative elements, they covered the steps of the stairs with tiles, and the old wooden objects were set on fire. If I enjoy some sympathy in the village, it’s not so much because I’m a writer and people saw me on TV, but precisely because “I didn’t spoil” and I kept things “that were once”.

Grandpa Toma died prematurely as a result of an accident in the forest, while cutting wood – an irony that left me inconsolable for a long time. In the meantime, I discovered what a complex material wood is, how varied it is depending on the essence, how fragile (vulnerable to water, sun, decay, mold) and at the same time how solid (taken care of, it lasts for hundreds of years). I often think that grandfather would have liked to see what I did in his absence, maybe he would have been proud of me. Because refurbishing and reinventing old objects is not just a practical activity and it’s not just about personal taste, it’s also the expression of admiration, love, longing for those before. Which are like wood.